Via www.patrickhruby.net

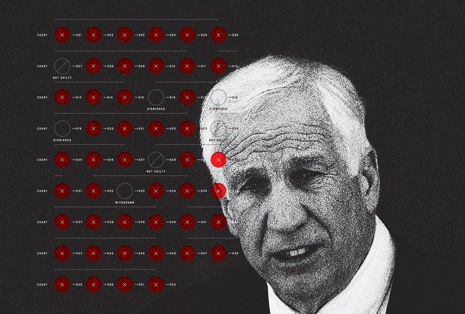

For Chris Gavagan, the ongoing Penn State football child sex abuse scandal looks all too familiar.

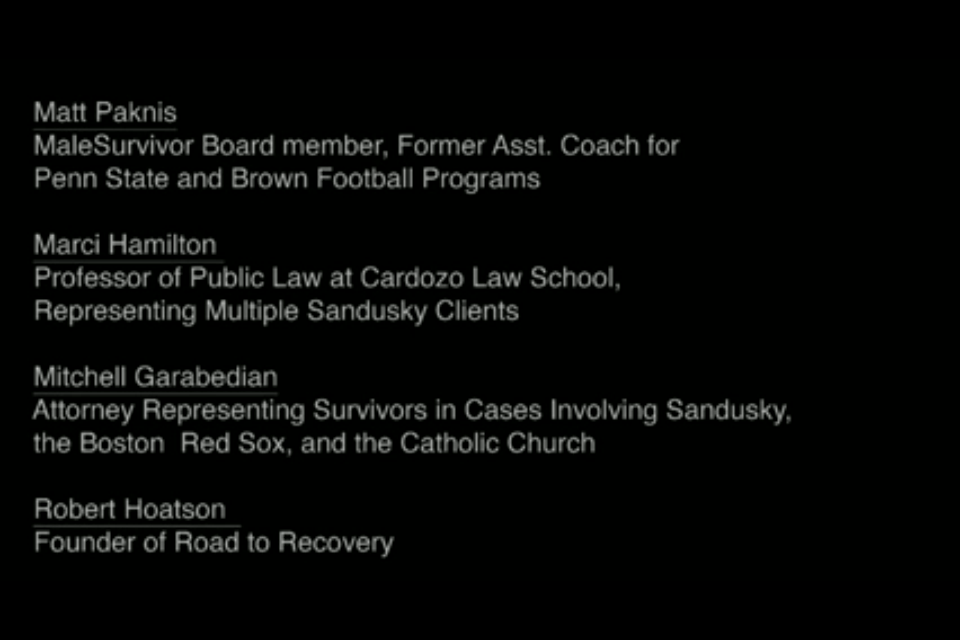

A Brooklyn-based filmmaker, Gavagan is working on Coached Into Silence, a documentary about sexual abuse in sports that includes interviews with experts, victims, and a roller hockey coach Gavagan claims abused him when he was a teenager.

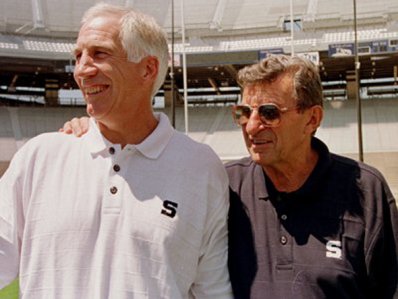

To understand how Penn State fits into the larger context of sexual abuse by coaches—as well as how the university’s leaders could display what the Freeh report termed a “total disregard for the safety and welfare of Jerry Sandusky’s child victims”— I recently spoke with Gavagan for an Atlantic online Q&A about the report, Joe Paterno and where the school goes from here.

Below are additional, previously unpublished items from that interview:

The Penn State board said it accepts “full responsibility” for failures that occurred, yet only one board member has stepped down. Paterno’s family and lawyers for other Penn State officials insist they did nothing wrong. How common is that kind of reaction from the people and organizations responsible for children’s welfare when wrongdoing and cover-ups are exposed?

With a Federal investigation still ongoing, much of this story is yet to be told. In general, institutions have adopted the deny what you can, admit what you must strategy. In one of the cases in the film, it was only after the coach who made a school a powerhouse for 30 years passed away that the school acknowledged that there were credible reports of sexual abuse of students. Not so coincidentally, this acknowledgment occurred after the statute of limitations on these crimes had passed.

In many cases, you also see similar “cherry-picked” information, such as Penn State’s decisions being made based on Seasock’s psychological report, rather than Dr. Chambers’ report. Loyalists who will back up the school’s version of events are pushed to the forefront, while those who line up against them are discredited.

Still, one need only look at each individual Olympic national governing body, sport by sport, to see the gamut of reactions to allegations of sexual abuse. Sometimes when a high profile program — USA Swimming, USA Gymnastics — is exposed for having ‘mishandled’ sexually abusing coaches within their ranks, those programs have learned from their mistakes, adopting a more proactive stance toward prevention. Many other institutions have responded by reexamining their own policies regarding, among other things, the mandated reporting of child sexual abuse.

Based on what you’ve seen in other cases, what do you expect the ultimate outcome of the legal process to be? Will people besides Jerry Sandusky go to jail?

Anything can happen when a case is handed over to a jury, but from the evidence that has been made public via the grand jury and the Freeh report, it appears quite clear that [Penn State athletic director] Tim Curley and [vice president Gary] Schultz perjured themselves. It is also clear, in denying any knowledge of the 1998 incident involving Sandusky, that Joe Paterno himself lied to the Grand Jury.

Were the coach alive today, I do believe that after the release of the Freeh report there would have been no way for him to avoid being charged with perjury.

What are the most important lessons Penn State can draw from the Freeh Report? What are the most important lessons society can draw?

For society as a whole, I think the most valuable way to see the Freeh report is as a dye-injected MRI through which we can learn more about a disease — the disease of willful institutional silence regarding the sexual abuse of children.

The has report has given us a clearer — though still imperfect and incomplete — picture of how a coverup like this can and does occur so often. It illustrates the positions where the decisions are made, the thought processes that led to those decisions and how very bright people chose to take the legally and ethically wrong path.

What steps can and should Penn State take now and in the future to prevent this from happening again, and also to address the damage done to Sandusky’s victims?

A change in the culture surrounding Penn State is a must, which is much, much easier said than done when the defining moment of a university’s week includes over a hundred thousand screaming “We Are …”

Having met many residents of State College and nearby Bellefonte throughout the course of the trial, I have seen people who are already having to come to grips with the complicated relationship between the geographical area and the university. As one elderly, dyed-in-Navy-and-White supporter told me “Love the Lion, hate the lies.” I admire that. And to that end, no less than full disclosure will do. I am all in favor of an international style truth and reconciliation commission

The soil in State College will remain toxic until the entire truth comes out. Until that time, the foundation is cracked. To build upon a foundation of lies, as shown so clearly in the Freeh report, only guarantees your eventual collapse.

As someone who has been a victim of coach sex abuse, how did the Freeh Report affect you emotionally? Do you have any insight into the sort of emotional impact the report’s release might have on other victims, including those of Sandusky?

Preproduction on Coached into Silence began in the Spring of 2009, with with the first interview shot in November of 2009. That means that through our research and ongoing filming, we have lived with all aspects of the sexual abuse of children by coaches every day for three years. Even more personally, I have dealt with life after sexual abuse for the last 20 years. Far from being jaded by being steeped in this issue so deeply for so long, through the anguish of every victim that I speak to the loss is made fresh and real all over again.

The Freeh report, when coupled with what will likely amount to a life sentence for a highly-respected and powerful man who used his position to prey on children, provides a measure of empowerment in seeing that (a) the victims were (eventually) believed; and (b) consequences are occuring.

When it comes to the unbelievably courageous young men that took the stand and faced their abuser — as well as all other unnamed victims of Jerry Sandusky that will never have their photographs projected on a screen in the Centre County courthouse — my hope is that the verdict brought them hope.

What I know is that somewhere, sleeping peacefully in their bed the night the verdict was handed down, the next victim of Jerry Sandusky just gets to be a child instead. No thanks to the powerful men who ran Penn State — who would have sacrificed that boy on their pigskin altar — but with all credit to those courageous young men who took the stand, who looked the devil in the face and spoke the truth in Bellefonte, PA.

Should the school end its football program? Why or why not?

Many will speak of the unfortunate athletes who would lose the opportunity afforded by their scholarships. My heart goes out to any innocent party that could be counted as collateral damage of this coverup, but the responsibility for the trickle down effect of these crimes lies with those who committed, enabled and covered them up, not those who hand out justice for those crimes.

In my opinion, if children have been raped on your campus, on your watch, you forfeit the right to carry on playing games until a complete overhaul in the way that you do business has been achieved. Calling a billion dollar football-industrial-complex a game may seem naive, but contrary to the prevailing attitudes, that is still what football is.

I don’t believe the program should be ended. Suspension for a period of years? I believe that the NCAA will weigh in very harshly over violations of the Clery act alone.

(Editor’s note: interview was conducted before the NCAA’s levying of penalties on Penn State football).

An institution such as Penn State has learned the hard way that they must bring the same the same transparency, the same level of vigilance, the same strict enforcement to crimes committed on their campus as they have tried to bring to NCAA violations. As detailed in the Freeh report, when labeling a sports agent who bought one of their football players $400 worth of clothing “persona non grata” and banning him from campus, Spanier and his cohorts acted like Michael Corleone. When they were faced with one of their own raping children on their hallowed grounds, when it mattered most … they were Fredo.

The investigation was deep in the places that it dug, but it was not nearly wide enough to tell anything approaching the full story. The bulk of this story, and it’s corresponding missing 30 years, is still to be told.

There was a memorable self-portrait from the troubled hockey genius who passed through New York a decade ago, Theo Fleury, who tried to explain an endless battle with alcohol and drugs with this poignant observation: “You’re only as sick as your secrets,” he said.And so there was Keyon Dooling, just three months ago, back home in Florida after signing a one-year, $1 million invitation to return to the Boston Celtics and making plans to head north for pre-camp workouts. The only problem: He was tired of the NBA life. Indeed, he felt forced into it.

There was a memorable self-portrait from the troubled hockey genius who passed through New York a decade ago, Theo Fleury, who tried to explain an endless battle with alcohol and drugs with this poignant observation: “You’re only as sick as your secrets,” he said.And so there was Keyon Dooling, just three months ago, back home in Florida after signing a one-year, $1 million invitation to return to the Boston Celtics and making plans to head north for pre-camp workouts. The only problem: He was tired of the NBA life. Indeed, he felt forced into it.