Could the Penn State Scandal Happen Somewhere Else? Definitely.

/ Coached into Silence director Chris Gavagan ’s interview with The Atlantic

Coached into Silence director Chris Gavagan ’s interview with The Atlantic

With the release of a damning, 267-page investigative report compiled by former FBI director Louis Freeh, the ongoing child sex abuse scandal engulfing Penn State University and former football coach Joe Paterno went from bad to worse, with possible negligence involving the sex crimes perpetrated by former defensive coordinator Jerry Sandusky giving way to a probable cover-up.

For Chis Gavagan, however, the contents of the Freeh report were hardly surprising.

A Brooklyn-based filmmaker, Gavagan is working on Coached Into Silence, a documentary about sexual abuse in sports that includes interviews with experts, victims, and a roller hockey coach Gavagan claims abused him when he was a teenager.

To understand how Penn State fits into the larger context of sexual abuse by coaches—as well as how the university’s leaders could display what Freeh termed a “total disregard for the safety and welfare of Sandusky’s child victims“—The Atlantic spoke with Gavagan about the report, Paterno, and where the school goes from here.

What similarities do you see between the Penn State depicted in the Freeh Report and the cases of child sex abuse by sports coaches documented in your film?

You could white out every proper name in the Freeh report and apply it to institutions all over this country that have failed in their responsibility to protect children. Time after time, the evidence has shown the most powerful and influential decision-makers circling the wagons and conspiring to decide, “How are we going to handle this?”

Victims are the last possible priority. Over and over, you see the drive to keep it quiet, to put it “behind us” with the fewest possible people being aware of it. In many cases—particularly at schools whose pristine reputation is paramount—rather than making a successful coach go away, they have made an accuser or the accusations go away.

In one elite prep school featured in the film, several students who came forward about abuse they suffered were quietly dismissed. In other cases, there have been payments handed out, “hush money” to convince a parent pushing the issue to relent.

It would shock me if the same tactics have not been put into play with Penn State over the decades of Jerry Sandusky’s involvement with the program, which began in the late 1960’s.

What differences do you see between Penn State and the cases you’ve covered?

The difference is the documentation. In most other cases, there will never be a report. We will never see this evidence. We will never be privy to these discussions. Without the national spotlight, most of these institutions have been able to avoid the scrutiny of such an investigation. Often, a loophole in the law — such as widely varying state-by-state statutes of limitations—can provide another shield. If an institution can avoid, delay and intimidate long enough, they can make Penn State [vice president Gary] Schultz’ 1998 e-mail wish “I hope it is all behind us” a legal reality.

Prior to the ubiquity of email, an institution would have just solved much of this problem with payoff for an accuser and a shredder for the incriminating documentation. In some ways, we are fortunate that technology has created more of a trail in these cases.

Generally speaking, how does something like this happen?

It takes a village to enable a sexual predator to continue unfettered for so long. The combination of ignorance of warning signs and willfully hidden information are necessary for these abuses to go on for decades.

Pillars of the community are given much more of a benefit of the doubt, but what has been demonstrated, unfortunately, is that nobody can be considered beyond reproach. The greatest masks of all are apparent good intentions and a smile. This is one of the most insidious aspects of these crimes. The stranger in the trench coat preying on children is the rarest of cases—the overwhelming majority are perpetrated by someone who is both trusted and known to the child.

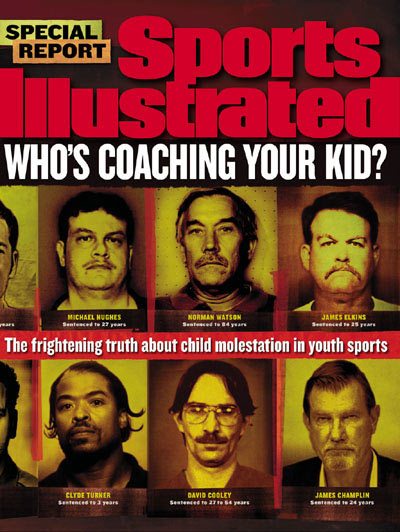

In our film, we discussed with former Sports Illustrated editor Don Yaeger his process of researching his1999 cover article “Every Parent’s Nightmare.” In our interview, he quotes a pedophile as calling coaching “the last great candy store of opportunity.” Not only did the most powerful men at Penn State choose not to shut down Sandusky’s candy store when it was brought to their attention, but by allowing his continued access to all things Penn State they went above and beyond to ensure that it remained open for business and that the shelves were stocked with the sweetest bait a young boy could imagine.

Which specific details of the Freeh report most stood out to you, and why?

The coded, callous discussions of incidents that Schultz called “at worst sexual improprieties”—and the talk of needing to clarify to Sandusky his “guests’ use of the facilities”—is appalling. They refer to a child victim of rape as if he were a kid being punished for peeing in the pool. It shows a complete and utter disregard for other human beings.

The nameless boy in the shower was someone’s child.

Also, the fact that information was withheld from the board right until the last possible moment, time and time again, demonstrates the danger of a lack of accountability and oversight. [Penn State president Graham] Spanier, [athletic director Tim] Curley, and Schultz come across as the last men shouting that the Titanic is unsinkable, even as their lungs are filling with frigid water of the North Atlantic.

How does the disregard for children happen?

More often than not, this kind of disregard occurs in tiny dehumanizing increments. For a human being, no matter what is at stake to professionally or financially, to take actions that enable these abuses to continue, they must begin by not seeing the victim as a human. The farther you get away from that flesh and blood child—nameless and faceless—the easier it is for you to proceed.

There is a reason that the prosecutors in the Sandusky trial opened their case by showing photographs of the victims at the ages that they were when these crimes were committed against them—because it works. I was sitting in that courtroom, and to be forced to face the very real, very human toll of these crimes is unbelievably powerful.

The men in power at Penn State did not have to face that. They faced words, they faced an idea, and by facing only that I believe they were able to discount, to some extent, the horrors that were being committed on their watch. There are things that one must lie to themselves about in order to be a part of, if you are to live with yourself. I would imagine that sacrificing a child to the “greater good” of an institution is one such case.

The Freeh report concluded that Joe Paterno and other top Penn State officials covered up the sex abuse allegations against Sandusky because they were afraid of “bad publicity.” Is that unusual? Why or why not?

In the vast majority of these cases, “bad publicity”—and all the considerations that entails, specifically in terms of financial backlash—is the immediate concern.

For example, when you run an elite prep school and charge $33,000 a year for tuition—like one of the schools featured in our film—administrators will go to great lengths to prevent any evidence from coming out that could tarnish their reputation and thereby handicap their ability to charge such an astronomical amount. Schools also rely heavily on alumni donations. How willing do you think their alumni would be to write out generous checks if they were aware that some portion of that donation was going to fight to keep sex abuse cases from going to trial?

Spanier acknowledging in the Freeh report that their decision not to go to the proper authorities leaves them vulnerable is a rare peak behind the curtain of all decision-makers who have chosen the same course of action—or inaction. They explicitly knew the risks, yet they did it anyway.

If there were a fire on campus, there would have been no debate as to “how are we going to handle this?” The proper authorities to handle the specific situation would have been called immediately.

One of the most heartbreaking things in the Freeh report involves janitors who saw Sandusky molesting a boy in the Penn State football showers but did not report the incident for fear of losing their jobs. Was their fear reasonable? What kind of reaction do child sex abuse whistleblowers typically face?

Their fears were unfortunate, but more than reasonable. To ask the lowest men on the totem pole to be heroes where “great men” have failed is unfair. The lower you rank, the heavier the pressure of the edifice above you. The little people get crushed—and who can rank lower than a child? Powerless. No money. No influence. The greatest action taken in your defense by anyone at Penn State was a slammed locker.

In a case featured in the film, it was the assistant coach who was the whistleblower, going to his superiors to report what he knew to be credible accusations against his head coach. As thanks for his speaking out, the administration of the school began a smear campaign against the assistant in the press, even going so far as to remove the whistleblower’s picture from the school’s hall of fame, while the picture of the head coach—who would eventually plead guilty to two counts of child rape—still smiled from his plaque within a glass case.

Personally, my own experience of reporting my coach and abuser to the league is both subjective prism through which I view reporting, and also a glimpse of the pressures that can be brought to bear. Although the director of the league believed me when I reported my coach, the next words out of his mouth were problematic: “I know you love this league too … and when this gets out they’re going to shut us down.” No so subtly, the victim had been handed responsibility for the potential closing of his beloved league. They dismissed the coach that night, but did no more. During the production of Coached Into Silence, I would discover that he took his whistle six miles down the road and continued coaching for years. The statute of limitations in my home state of New York had expired, and there was nothing I could do.

The Freeh report also blamed a “culture of reverence for the football program.” What do you make of that?

In an interview that we conducted in 2009 with Cardozo law professor Marci Hamilton, she discusses the shadow side of a successful coach. Although a successful coach is a wonderful for any organization, there is a danger when that individual’s success has begun “a legacy of donations for the institution.” Sandusky masterfully exploited the cover provided by his own gridiron success, and those in power who surrounded him willingly provided the ongoing shield with the Penn State imprimatur—with one apparent and unenforced condition: Don’t do it here.

We have cases in the film where the abusers have not just won many games or championships, but are gold medal-winners or enshrined in their sport’s Hall of Fame. For a particular institution or sport to admit and acknowledge abuse or a problem with someone who has risen to these heights and has been given every accolade imaginable takes an extraordinary amount of fortitude.

Unfortunately, that kind of courage is rare. More often than not, a literal or figurative cost benefit analysis is done, an institution tabulates the price of potential lawsuits, and the decision is made to do all that is within their power to make the problem go away without reporting it to the police.

A report estimated that the Sandusky case could ultimately cost Penn State $100 million in civil damages. What is the psychological and emotional cost to Sandusky’s victims?

The true human cost will never be accurately tallied. Having personally lived through the effects of these abuses on a victim—and studied all that there is to study about them—I can say that not all who fall prey will live long enough to be called a “survivor.” Among Sandusky’s victims, there are bound to be those who have taken their secret shame to the grave, dying by the drugs or alcohol that they took to cope with the abuse, or succumbing to depression and suicide. The suicide rate among victims is many, many times higher than average.

What lessons can Penn State—and the rest of us—learn from this tragedy?

When any man—or any college sports program—becomes more powerful than the institution itself, corruption is sure to follow.

As someone who remains a true sports fan and has enjoyed the benefits of being involved, I can’t demonize that world. Yet when any aspect of an organization becomes a money-printing machine, the tail begins to wag the dog. For example, Phil Knight’s hero worship [of Paterno] cannot be viewed independently of knowing where his bread was buttered.

Penn State remains an incredible educational institution, turning out many of this country’s best and brightest minds. But some of the deepest soul searching that must be done at the school regards exactly how much power they have ceded to football. They have sacrificed too much at the altar of the sport.

Should Penn State take down its on-campus statue of Paterno?

To choose to continue to honor the man as the winningest football coach and the architect of his “grand experiment” is to ignore this truth: For all of the good he may have done, for all the lives that he may have impacted in a positive way, his grand experiment was a failure. The cult of personality, the total lack of accountability, the man who could tell his superiors exactly when he would be stepping down existed in a poisoned atmosphere of his own creation. The power centralized in one man, immortalized in bronze, made a true chain of command, of checks and balances, impossible. When it is a controversial decision to paint over someone’s halo, we are ignoring the man’s humanity, not honoring it. The disregard for the humanity of the victims—”some Second Mile kid” and “the boy in the shower”—is how this was allowed to occur in the first place.

My wish is for the statue to be taken down and returned to the workshop where it was created, then have Paterno’s skyward-pointing index finger repositioned in front of his lips — the exhale of a quiet, craven “Shhhhh.” Put that new version on a flatbed truck and tour the nation, with those who have survived childhood sexual abuse speaking at every stop to educate and raise awareness of the issue while warning against the hubris that led a “great man” to believe that his own reputation mattered more that the lives of children.

I didn’t know what to expect, or when to expect it. I thought I might read while I waited so I brought a book with me, only two chapters remaining. I planned to write more, so thank your lucky stars, this entry could have been several thousand words longer. Instead, the interaction of the two characters in the picture above provided the entertainment.

I didn’t know what to expect, or when to expect it. I thought I might read while I waited so I brought a book with me, only two chapters remaining. I planned to write more, so thank your lucky stars, this entry could have been several thousand words longer. Instead, the interaction of the two characters in the picture above provided the entertainment.